WTF Are They?

Defining an Assault Rifles. For Reals.

Reading Time: 15-20 min

If you are new to the issue of assault rifles and gun control it may have been a surprise to learn how complicated it is to actually pin-down what one of these guns really is, both in terms of what they are called, what they actually do. Really; how hard can it be right?

Newb.

Scratch the surface of the question of assault rifles, at least in North America, and you will be smacked pretty quickly by a wave of bullshit, politics, and rhetoric. The majority of the problems around defining assault rifles, or “assault rifles” or “so-called” assault rifles, or maybe “tactical” rifles, or “sporting” rifles, or “black” rifles, are not actually practical issues. They are legal and public-relations based. This is fabricated complexity designed to gaslight the public and make legal restrictions less effective. Period

A great deal of the back-and-forth on names and characteristics which define assault weapons is about framing and re-framing in order to move the dial of public perception away from how dangerous they are, and what they are meant for. The names are really not important, or to be more accurate: the terminology only has importance in a few scenarios, but actually figuring out what these guns are or how dangerous they may be are not among them.

But do not be drawn into this bullshit. It is all just a smoke-screen. It is gaslighting.

You will find a deeper dive into the bullshit around labels and names, and how that all started, in the Birth of the Bullshit section. Here the focus is on the practical and functional views, on the things that actually matter: how they work and are used.

To be able to have meaningful discussion about what to do with these guns it is important that we understand what they really are, and that we can identify them from the other, and often less dangerous guns. To do that we need to be clear on what an assault rifle actually is, not what it’s called, and not how it looks.

The key is not in the name, and while the appearance does provide important clues to their purposes and uses, it is vital to focus on core functionality, and what they have been built to do.

What follows is a general, high-level explanation of what makes them what they are. This goes hand-in-hand with the Scalable Lethality article, which explains why the core functionality of an assault rifle is so deadly.

Fortunately, if you are in a rush the topline info is simple:

Assault rifles are a type of firearm developed for combat applications. They are highly optimized to provide a specific type of firepower: a high volume of sustained, and very effective rapid-fire. This results from combination of several functionalities that, when found in a single gun, distinguish it from other weapons like bolt-action or lever-action rifles, etc. The resulting capacity for sustained and effecive rapid-fire is what allows the massive scaling-up of violence that is not possible with other firearms.

There are 3 fundamental functional characteristics that combine to truly define an assault rifle:

• Capable of Rapid-fire

• Fires medium/centerfire cartridges.

• Uses detachable magazines (often high capacity)

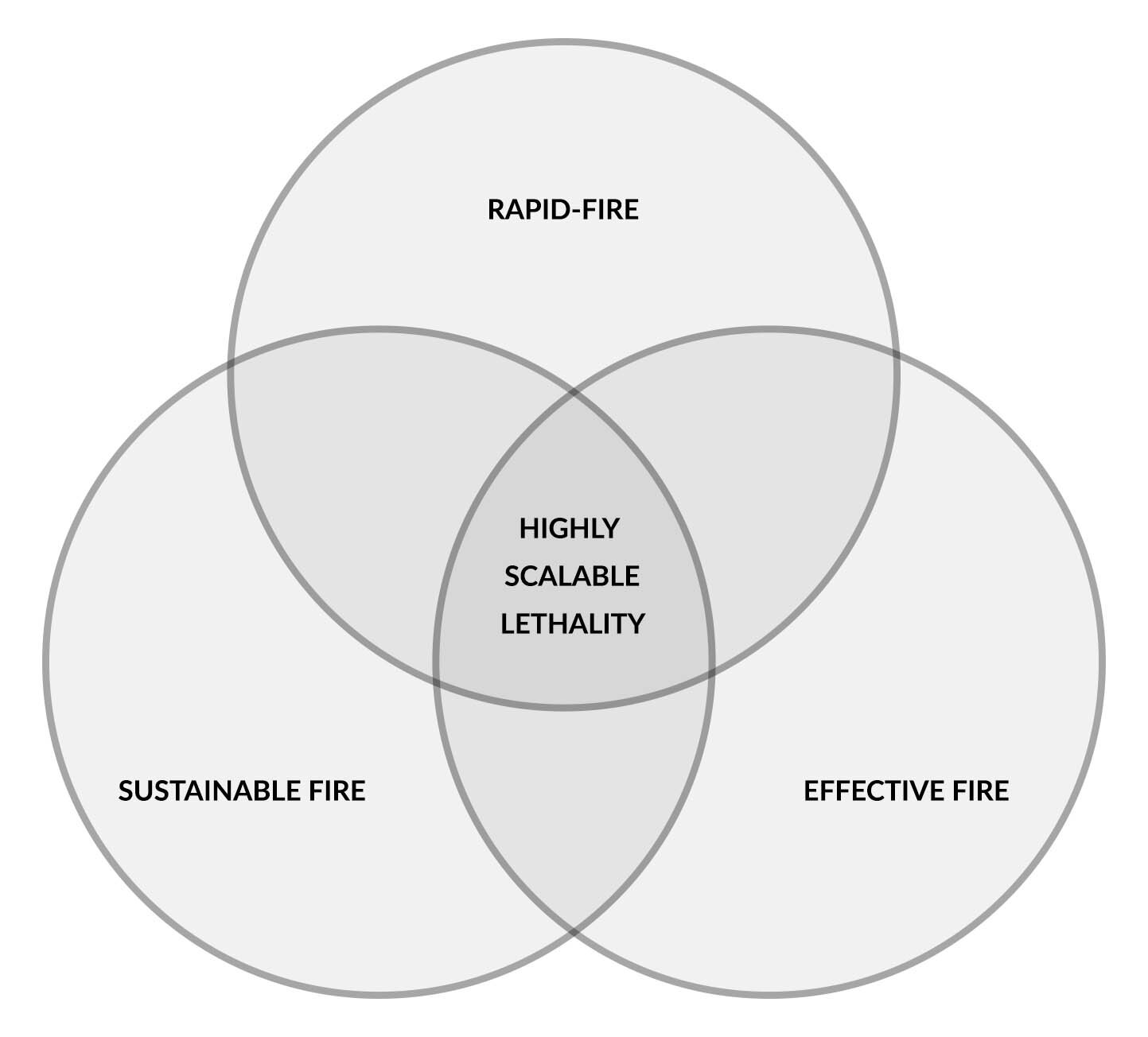

These in turn drive three inter-connected qualities of fire that together make for highly scalable lethality:

It is the combination of these 3 qualities of fire that make for highly scalable lethality - the ability to kill on a scale far beyond what a single person can do with other firearms.

Assault rifles are designed, built, and highly tested to perform well in battlefields and every imaginable environment. This means they are also typically extremely robust and reliable.

This is part of the “sustainable” aspect of that deadly capacity, but the most important point about this is that assault rifles are exceptional at working well in just about any scenario or use-case, whereas most other weapons have a much narrower range of optimal usage. Most are far more sensitive to failure or reduced effectivenss due to changes in context, such as different ranges or shooting conditions (e.g wet, dirty, etc.).

This is an historically and functionally accurate picture of assault rifles, and these are the aspects that drive the details and appearance, and naming, not the other way around.

Origin of the Term and the Definition

The name "assault rifle" goes back a stretch, but it seems likely that the term was never intended to be anything other than good marketing. Much has been made of it since, but probably it just sounded cool, and has stuck.

The term and weapon share roots in WW2 Germany and with a particular weapon the Nazis designed and called the Sturmgewehr 44, or StG44, which literally translates to “assault rifle 44". It was a name which reflected its purpose - assault fire and general ass-kickery on the battlefield. Descriptive, sure, but if we consider how wartime Germany tended to roll when it came to propaganda, this was also probably mostly about PR and marketing. "Assault rifle” likely sounded cool then too, and also likely made the soldiers that got them feel pretty bad-ass. Well, the guns along with all the crystal meth they were jacked up on.

The OG assault rifle: the StG44. Source: Wikipedia

But the guns did more than sound cool, they worked extremely well and the design concept spread rapidly post WW2. The StG44 is the archetype of the modern assault rifle, in terms of both function and appearance. Note the iconic “banana clip” of the high-capacity detachable magazine, the rear pistol grip, the barrel shrouding to protect the shooters hands from getting burned on the barrel during rapid-firing.

This is also where many people, mainly the gun lobby, turn when trying to force a hardline definition on assault rifles. Logical enough, but there is no hard and fast reason why we have to stick very tightly to the specific design. It’s the way this weapon provides a function, the way it solves a set of problems that make it what it is, not exactly how it solves them. Saying that an assault rifle is only one that exactly matches the StG44 is like saying a car is only a car if it looks and functions like this one:

The 1885 Benz Motorcar. The OG automobile.

Sticking to that hardline is convenient for the gun lobby, but for reasons that have little to do with historicity.

In any case, the name itself was ultimately and always mostly just a tool for communications, and marketing. But it still sounds bad-ass.

So what made the StG 44 different? Why was it made at all? Easy: high volumes of sustained, effective rapid-fire.

Prior to the StG44 and the advent of the assault rifles soldiers were regularly issued one of a few types of guns. The most standard were probably the battle rifle and the carbine.

Battle rifles were (and still are) the bigger, heavier, and more powerful of the two, and had greater ranges and usually greater stopping power. Carbines were smaller, lighter, and more maneuverable - so good for trench and closer-quarter warfare. The downside was less range and stopping power. Neither was very well optimized for sustained rapid-fire, and a high volume of effective rapid-fire is extremely valuable when the goal is to have each of your soldiers kill or injure as many enemy as possible, and as quickly as possible.

Another common type of weapon was the submachine gun, which were small, very good at rapid-fire, and very effective at short ranges, but lacked the longer range and power of the battle rifles or the carbines. There were also true automatic weapons — machine guns — that were very rapid fire and typically very powerful, but that tended to be large and heavy, often needing a crew to operate.

After that there were (and still are) a mish-mash of pistols, shotguns, and other special purpose weapons, but in the trenches — figuratively and literally — the rifle and carbine had been the go-to and were the most versatile and deadly. To that point anyway.

WW2: Soldier with an M1 battle rifle, which is typical of the era. Source: Wikipedia

The StG44 was something different. It was designed to blend several of the more effective features/functions of the standard-issue weapons into a single, more ideal multi-purpose killing tool. One that could shoot very quickly but with far greater control and accuracy, as well as having good range and stopping power. This meant developing both a new weapon but also an optimized cartridge (bullet) as well. Providing the right balance came down to the characteristics that the StG44 united, those three key aspects mentioned above:

Medium sized cartridge

Detachable high capacity magazine

Capable of rapid-fire (The StG was full-auto, but more on that in a sec)

There are other design elements about the StG44 - like the pistol grip for example - that are also important because they increase lethal effectiveness, however that is getting into optimization and enhancements, not core functionality. Check the Scalable Lethality and Bullshit is in the Eye of The Beholder articles for more on that.

The three functional characteristics , when combined in one gun, create the core capacity that made these guns particularly effective, and that have become the least argued and most accepted characteristics of any assault rifle. And even less argued, if you swap “rapid-fire” for “full-auto”, but again - that’s coming up.

The reason again is that this combination provides the necessary components for sustained, effective rapid-fire, which is the recipe for highly scalable lethality, and the recipe that makes it possible for one person to kill many with far greater ease than any other firearm.

If that doesn’t make sense yet there is lots more on this concept in the Scalable Lethality section too.

Post WW2

Those three functions still define the type today - generally, if not always strictly legally. The name, and the parts that make this possible are not what is important. The functions they serve are what matter.

The StG-44 did things in a certain way as a result of a combination of characteristics. The combination is what made it more dangerous, more lethal, not the individual factors. The gun as a functional system is the important thing, and this is extremely important to keep in mind in order to assess the risks and benefits of these weapons. I’ll put it this way:

The single most important factor about assault rifles is that there is no single most important factor.

Getting caught up by specifics and losing sight of this is how we get misled on the real risks. What matters is how all of the aspects combine to make that highly scalable lethality possible.

The importance of function and of a systemic view of the weapons is captured nicely in the definition of assault rifle used by DARPA (The Defense Advanced Research Project Agency).

DARPA is a major "R&D" arm of the US military, and they were responsible for testing the AR15/M16 prior to its adoption - which was during the Vietnam War. This was done under the umbrella of “Project Agile”. The following definition is the one they used, and is taken from a de-classified 1963 quarterly project report :

"Assault Rifle - This task was initiated to provide a weapon better suited to the individual soldier. A lighter, more effective weapon/ammunition system capable of delivering accurately aimed, high rates of fire at fleeing targets is desired.”

Along with that we also have US Army's notion of "assault fire' and "quick fire' which inform the definition too, and also demand the same sort of tool:

"The three primary ways of directing fire with a rile are to: aim through the sights, hold the weapon in an an underarm position and use instinct, bullet strike, or tracers to direct fire (assault fire); or bring the rifle to the shoulder but look over the sights as the rifle is pointed in the direction of the target (quick fire)." (Emphasis mine)

--Source: TC-7-9 Infantry Live-Fire Training; Headquarters, Department of the Army

You will note that neither focuses on particulars of the gun, on how exactly it does the job. They don’t specify calibers, things like grip design, or precise rate or mechanism of fire, or anything of the sort: because all that matters is that it does the job: sustained, effective rapid-fire.

That system of inter-connected characteristic functions in the StG44 proved to be very successful for that kind of shooting and killing. The StG44 became the template for the modern assault rifle - which are now the de-facto standard issue weapon of armies and police forces all around the world. The influence is probably most evident in the iconic AK47 assault rifle, which the StG 44 clearly inspired (quite literally - interesting story, but not for here) but it’s offspring include them all.

An AK47 assault rifle. The resemblance to the StG44 is clear. (Source: Wikipedia)

Again, it is the way the various aspects of these guns work together, the system they form, that makes them dangerous - not just any one thing. The gun-lobby seems intent on everyone losing sight of this through their concerted efforts to make full-auto crucial to the definition, or over-emphasis on optimizations like grips and stocks.

In any case, the StG44 defined the archetype of function, and the iconic appearance we have all come to associate with an assault rifle, which is partly why so many gun proponents point back to it like it’s a stone tablet.

A Short Tour Through the Key Factors:

Y ou will find a much deeper dive on what folows in the Assault Rifles: The 3-Part Recipe for Scalable Lethality section, but what follows is a quicker, overview kinda of tour. It helps explain why these three things are vital to a proper definition, and how they combine to make these weapons so dangerous.

Medium Sized Cartridge

The impacts here on lethal effectivness are mostly obvious, but there are couple that are surprisingly important and somewhat non-obvious, at least to non-experts.

I use the more correct term of “medium cartridge” but many more modern definitions of assault rifles will often talk about “centerfire” cartridges instead of “medium" so that should be cleared up a bit.

Centerfire is actually the category of almost all bullets except for some very small ones (.22 is a common bullet that works differently) and some shotgun shells, but the technical differences don't matter that much here. In the context of assault rifles referring to “centerfire” guns is usually just a short-hand way of talking about “serious” guns versus one’s that are considered low-powered “plinkers”.

Basically, talking about centerfire guns is a way of excluding shotguns, and guns that shoot lower-powered rimfire .22 calibre cartridges. It is true that any centerfire rifle that also matches the other criteria of detachable magazine and capable of rapid-fire is extremely dangerous, and may function perfectly well as an assault rifle, for the purpose of really understanding why the category of assault rifles are the most dangerous guns the "medium" thing can actually be quite important. It is also worth noting that just because a gun is chambered for .22 “plinking” bullets, that does not mean they are not potentially very deadly weapons too. In fact, they may be among the most commonly used for gun homicides.

How “powerful” or “big” a bullet is can have obvious impact on lethality, but what is less obvious — and rarely mentioned by the gun folks because it works against their case for assault rifles — is that bigger badder bullets can actually reduce the overall lethality of a firearm.

Again, the Assault Rifles: A 3-Part Recipe for Scalable Lethality article has a lot more on this, but the short version is bullets can be a lot smaller and still be extremely powerful if they are high-velocity, and can actually be quite a bit more lethal than larger but slower ones, largely due to reduced recoil, but for logistical reasons as well.

This is especially true with rapid-fire weapons, and that is why assault rifles and the ammunition they fire we were developed together, in a chicken-or-the-egg kinda way.

Here is a picture that makes it pretty clear why it’s called a “medium” cartridge:

7.62mm NATO, 5.56mm NATO, 9mm NATO rounds. The middle is the assault rifle round. (Source: Wikipedia)

You can see the medium cartridge, the 5.56mm NATO, is considerably smaller (and lighter) than the battle rifle ammunition, but is still quite a bit larger than the pistol calibre. This ammo, along with modern assault rifle, was designed around the need for what is essentially the “Goldilocks" bullet between the lower powered pistol cartridges (far right) and the heavier and larger rounds common to standard issue battle rifles (far left).

It was designed to have more stopping power than a pistol, but still have reduced recoil, making shooting — especially rapid fire shooting — more controllable, and thus deadlier. It was also designed to be light, to allow carrying more ammo (a lot more actually - which is hugely important) and to create more terrible wounds. And man did that work out well:

"Taking into account the greater lethality of the AR-15 rifle and improvements in accuracy and rate of fire in this weapon since 1959, in overall squad kill potential the AR-15 rifle is up to 5 times as effective as the M-14 rifle.” (emphasis mine)

— Report of the Special Subcommittee on the M-16 Rifle Program of the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives

So yeah, bigger is not always better. There are many aspects that come into play.

Probably the most clearly documented example of the chicken-and-the-egg process of developing the medium cartridge and the weapon platform for it is with AR15/M16 platform and the cartridge pictured in the middle above, the 5.56mm NATO round.

That assault rifle and ammunition were literally built around each other, but in many ways the driving force was the bullet more than the firearm, and this is because the military understood the importance of the cartridge characteristics to defining the overall lethality, and the systemic nature of that lethality.

There was a list of parameters the US military came up with — lethal objectives the bullet was asked to meet — and the gun was engineered (adapted really) to fire them and help meet those, as well as other combat-related goals (like firing at those fleeing targets).

The AR-15/M16 and the 5.56mm cartridge were built to fit perfectly together, and they definitely got that right.

Detachable (High Capacity) Magazine

The invention of detachable box magazines was a game changer in the firepower business. The reason is simple: sustainability. They make it much faster to reload, and by increasing capacity they reduce the frequency of reloading dramatically.

Detachable magazines also make the logistics of fielding a lot of ammo much simpler and more manageable. More bullets, delivered much faster, for longer.

Detachable box mags are what most people imagine when they hear about a gun magazine, or “mag”, or “clip”. You probably imagine something like the ones pictured below - they are the most common style. “High capacity” is variable, but people usually think of them as holding 10 or more cartridges.

Assault rifle magazines more commonly hold 20, 30, or more rounds of ammunition. 50, and even 100 round magazines are available (including in Canada). Those have been popular with mass murderers in the last few years, by the way.

AR15 showing external magazines and the magazine well where they are inserted. (Source: Wikipedia)

All-in-all, the detachable magazine greatly increases the amount of bullets that one person can effectively field and fire, and also dramatically increases the ability to sustain a high rate of fire for longer periods of time. They unlock massive amounts of potential firepower, and that applies for any weapon that uses them, not just assault rifles.

But detachable magazine are especially important for a weapon that is intended and optimized for sustained rapid-fire, be that assault fire, or covering or suppressing fire (the prime uses for fully-automatic firing), or for just trying to kill a lot of innocent people in a short period of time. In any event, rapid-fire runs through ammo, well, rapidly. Having more is key.

While ammo consumption is obviously higher with rapid-fire, do not be confused about how effective rapid-firing is done. Effective rapid and assault fire — and generally most fire intended to kill people — is not just high volume, indiscriminate, or wild. It is not often best served with fully-automatic fire either. That just wastes bullets.

The US Army Rifle and Carbine manual, and basically all modern military and combative training, reinforces this point, emphatically. In fact things like 3-round burst firing modes were specifically added to reduce the use of full-auto fire and the wasting of ammunition.

That is discussed more just below, but assault rifles definitely need more ammo on tap, and a quick way to reload. Thus they have detachable magazines, and high capacity ones in particular.

One point I want to really drive home though:

In terms of importance to the weapon’s lethality - both detachability and higher capacity matter, but only detachability is truly necessary to this picture.

Capacity is big, and certainly the anti-gun movements have fought to have high-capacity magazines prohibited (with moderate success at best). In what seems like a rare bit of shared perspective, the Canadian gun lobby also like to highlight high-capacity as more important (even while fighting against restriction on high-capacity magazines). That’s just bullshit on their part though.

That is because it is really the detachable factor that is vital to making weapons more dangerous. A detachable ammunition sources is what opens up the possibility of high-capacity in the first place, and creates the possibilities for reloading options that make sustainable fire remotely possible as well. The gun lobby know this and will fight forever to have detachable magazines protected from bans, even though that is where the real danger and value lie.

High-capacity is a major improvement and optimization to magazines, but that is all it is. So the gun lobby can pretend to care about a lot about it, but it’s another pawn in the game really. As well, they have workarounds that render restrictions moot anyway, so what do they really care? Polysesouvient has done a good job of breaking this particular bit of bullshit down. It’s worth a look.

Given how many different firearms, not just assault weapons, in fact use detachable magazines it is not surprising the the gun lobby has tried to de-emphasize this in favour of pointing fingers at high-capacity mags, but it all comes down to bullshit to protect guns, not people.

There is a lot more to be said on this, and of course there are other factors that come into the the picture, particularly here Canada, but that is the crux of it with detachable mags.

Capable of Rapid-Fire

This one we have to spend a bit more time on, but almost less for the importance it has to the system of lethal function of an assault rifle, and more because of the importance placed on the issue of selective-fire by the gun lobby.

For them, the third pillar of the definition is not “rapid-fire” it is fully automatic fire. If you are really unsure about what full-auto means, and how it differs from semi-automatic fire, I have a short side-trip section that explains it more fully, but the gun lobby has worked to make this aspect important as part of the effort to try and "define away" the entire category of civilian assault rifles, all in an effort to avoid having them banned. This, even though it was the semi-automatic versions that were almost invariably used in mass shootings that created the impetus for bans. Class all the way.

Full-auto, as a characteristic function, is used to deceive the general public about where the real danger lies. It is used to hide the fact that the real danger of scalable lethality resides very firmly within semi-automatic “modern sporting” rifles — which is one of the most popular euphemisms for civilian assault rifles. Military-optimized assault rifles are not the only ones capable of rapid-fire though, there are many that are less obvious and less purpose-tuned but are nonetheless capable rifles. Many of these are ones that the gun lobby misleadingly use to try and downplay the risks, for example the ever-popular Ruger Mini14 which seems to be the poster child for this kind of bullshit.

The gun lobby leans hard on the "historical" definition of the StG44 and insist upon full-auto firing for a “real” assault rifle, but as we look at in The Birth of the Bullshit , it wasn't always that way. It also seems very clear from the definitions shared above that the people that developed these guns certainly weren’t particularly focused on full-auto fire. A fair question to ask is why the change of heart and focus for the gun crowd? An easy answer there: mass shootings and bans - explored in the link just above quite a bit more.

If we skip some serious politics and focus instead on function, then just thinking in terms of rapid-fire, and specifically upon effective and sustained rapid-fire, matches how assaults rifles are actually used, and also matches definitions the gun lobby and industry quite happily used for decades.

Again, if you are not clear on what rapid-fire really is, and the differences between full-auto and semi-automatic weapons and firing modes, I really suggest you check the section devoted to clearing that up. For now I’ll assume you understand it and the implications of the different modes and just focus on applications here.

Full Auto and Semi-Automatic Fire - It’s all Rapid in the End.

The question is not whether or not rapid shooting is important. That’s pretty obvious, and if not it’s well covered in the section on Scalable Lethality too. The real question is: how rapid is rapid enough? How fast does it have to be to be considered extremely dangerous? What else has to be accounted for in order to properly answer that? (remember, no single factor). Let’s look at the variables:

Full-auto is when a gun will continue to fire bullets for as long as the trigger is pulled, till it runs out of bullets or has a breakdown. It is definitely “rapid-fire”. For example, the M16/M4 fire between 700-950 rounds per minute (rpm). That will empty a standard 30-round high-capacity magazine in a bit more than 2 seconds. But even full-on, purpose-built machine guns are rarely used that way, and for slightly complex reasons. What follows should get the main points across without the big slog, but all the details are covered more in Assault Rifles: The 3-Part Recipe for Scalable Lethality.

Certainly, there are occasions where just blasting away in full-auto, or at least long bursts of it anyway, are going to be an effective way of creating chaos and carnage. We’ve all seen it in movies, and even when it is not directly lethal that kind of volume of fire can be indirectly dangerous, and very unpredictable. There is no good use for it in civilian life to outweigh the danger, so it’s banned almost everywhere.

Here’s the thing though: outside of using it to make an enemy duck and cover and not shoot back at you, full-auto fire is just not that useful, and often highly discouraged by military and police training - because it just wastes bullets. It is not effective fire. It is also very hard on the gun, and cannot be sustained for long without a lot of engineering, and usually teamwork.

Outside of some use-cases in the military, and outside of “fish in a barrel” shooting situations, typically full-auto is used with careful control of the trigger to fire in short bursts, firing 3-5 rounds and then releasing the trigger. That is much more effective, so even in combat letting it rip in full-auto is rare, because it is generally less lethal, as well as being hard on the weapon.

What makes full-auto fire less lethal is inaccuracy stemming from the recoil of a shot. Every bullet fired makes the gun barrel jump around to some degree, and at 10-15 shots per second, that can be a lot of jumping, even with smaller bullets.

This is one of the major reasons why assault rifles were designed around a medium cartridge - to make sustained rapid firing more controllable by reducing recoil, but they wanted to do that without sacrificing the killing potential, as was the case with submachine guns and other smaller-calibre weapons. It is also why pistol grips (front and rear) as well as other design optimizations are so useful - but that’s not the real point here.

However, even with a less powerful medium cartridge, assault rifles still have enough recoil that long bursts of fire — typically anything more than 3-5 rounds — just get progressively less accurate, and less lethally effective - at least directly. This doesn’t mean there aren’t uses for cyclic fire, there certainly are - it’s just that directly killing people isn’t really the big one some would like you to think.

The primary alternative to automatic weapons are semi-automatics, where the gun fires one bullet per pull of the trigger. This is as fast as you can manage, one shot at at time. Non-gun people might tend to think that this is equal to slow. Nope.

The gun lobby often like the public to think it is slow too, but it isn’t - it is just slower. Usually. Sorta.

More on that soon, but for now: people typically consider semi-automatic rapid-fire to be about 45-60 rpm. That is pretty quick, but most shooters and semi-automatic rifles are capable of much higher rates when shooting in short rapid bursts, easily getting up to 200-300 rpm with no tricks or trouble at all. The less one cares about accuracy, the faster one can shoot too.

If a weapon has the option of switching between full-auto and semi-auto modes, which is far and away the most common for military assault rifles, it is called a selective-fire weapon. Because it is so common, “selective-fire” is how most gun people will refer to what many think of as "machine guns”. You may hear "automatic weapons” a lot too, but never "machine guns" from those in the know (unless they are actually talking machine guns)

A selective-fire AR-platform lower receiver, currently in full-auto mode. (Source: Wikipedia)

Worthy of note: selective fire is the only functional distinction between poster-child guns in the feature image: the civilian AR-15 and the military M16

Full-auto versus semi-automatic fire is based on mechanical differences, very small ones actually, and the physical mechanics of how the trigger is used. The point here is that those are the clear bright lines that divide the two types of guns - but the mechanical bits are the only place the difference is actually binary. Functionally, how the guns are used and how they can be used, is a lot less clearly defined. This is due to the limited effectiveness of full-auto fire when it comes to killing people, and also to the speed at which semi-automatics can fire. Those are fuzzy lines, at best, and this is why, in order to be more sensible, the definition of assault rifle has to be broadened back to something more viable - like the one DARPA used, for example.

Selective-Fire Isn’t Very

Source: Universal Pictures

Despite how the term may sound, and without care, full-auto is about the least “selective" you can get without just closing your eyes and firing away - which takes us back to the idea mentioned above about shooting in short bursts of rapid-fire.

The reason for both is weapon recoil, and how the movement caused by each shot makes the next shot harder and harder to aim well, especially when shooting rapidly. That difference, between how fast it can fire and how fast someone can aim and fire, is the difference between an automatic weapon’s cyclic rate — its “max speed” — and its effective rate of fire, which is a shit-ton slower. That’s how we end up with that “typical” semi-automatic rapid-fire rate of 45-60 rpm, that is the effective rate. The point to understand is that the effective rate is the same for full-auto rifles as well, except when firing in extremely short bursts.

Full-auto is fast remember - up to 900rpm - so that recoil problem stacks up quick, even with highly controllable modern weapons and ammunition. This why you sometimes hear full-auto shooting called “spray and pray”. Depending on the caliber and design of the weapon, most experts will tell you that even with a good assault rifle and cartridge combination, at any kind of range — say 20m or more — that anything after the first 1-2 shots is likely to be completely off target, and even if closer probably no more than 3-5 shots will be very useful - which is why the 3-round burst option was developed.

In any case, full-auto is rapid, no question, but so rapid that it can be challenging to make effective.

Slow and Steady Wins the Race.

In terms of actually trying to kill people — intentionally lethal shooting — short bursts of full-auto speed can be very effective, particularly in close-quarter combat, and when shooting at obscured targets that you cannot see well, or when shooting at dense groups of unarmed civilians that can’t easily get away - the horrific "fish in a barrel" scenario.

But the fact is that even in those moments, this kind of fire can often be replaced, and usually be improved upon, with sustained, controlled rapid semi-automatic fire, placing 1 or 2 shots with very high speed, precision, and much better accuracy. This is exactly what you see happening with well trained shooters everywhere.

Or in any John Wick movie.

Or in the newer Netflix movie Extraction. Or, really, any good modern combat movie.

Or just read up on a gun forum.

Or just ask the US Army. This is not exactly top secret stuff.

Here is the US Army manual for the AR platform assault rifle on the subject of rate of fire:

"Slow semiautomatic fire: 12-15 rpm. Rapid semiautomatic fire: “is approximately 45 rounds per minute and is typically used for multiple targets or combat scenarios where the Soldier does not have overmatch of the threat.” (Emphasis mine)

Source: TC-3-22.9 Rifle and Carbine: Headquarters, Department of the Army)

Having “overmatch” usually means fire superiority - basically, you have superior killing power and/or greater tactical control of the situation. Note that to achieve overmatch in combat or against multiple targets, they suggest cranking ‘er up to a whopping 45 rpm. That’s a long way from the 900 rpm of full-auto, even in bursts, and a long way from the 200-300rpm one can easily accomplish with semi-automatic burst-style rapid fire, and again - that is not even using tricks that will go much faster. So effective rapid-fire is surprisingly slow, at least to many non-gun experts.

Most of the time full-auto is just too fast. It just wastes ammunition, and you don’t need that much speed to get the job done. Accurate fire means you need less shots on target to be effective, especially with high powered cartridges.

This is particularly true when looking at the context of a mass shooter firing at unarmed civilians, when return fire is rarely a significant concern during the bulk of the event. While they must move quickly, they just typically don’t need to be quite as rushed as a soldier in combat that is being shot at. Spree-killers can be more methodical with less risk, although speed is still a critical factor in those situations.

And they know it too. Consider this from of one of the worst mass murderers in history, Anders Breivik, who used his (legally owned) Ruger Mini-14 semi-automatic assault rifle (and a handgun) to murder 69 people, mostly children.

From his ‘manifesto’:

"You don’t really need to practice on full auto mode. The most important thing is that you familiarise yourself with recoil in combination with high speed aiming. This can be done with semi automatic rifles….I legally own...a semi-automatic Ruger Mini 14 and have managed to familiarize myself with high speed target acquisition in relation to the recoil by firing one round at a time. Automatic mode is not practical for 5.56 and 7.65 assault rifles as it is more or less impossible to accurately hit a target while ‘spraying’ in one direction.” “As I have now acquired a legal semi automatic Ruger Mini 14 I can legally practice at the gun range. Full auto training is not really required.” (Emphasis mine)

So what is full-auto really most useful for? Here’s that Army rifle manual again:

"Automatic or Burst Fire: is when the Soldier is required to provide suppressive fires with accuracy, and the need for precise fires, although desired, is not as important. Automatic or burst fires drastically decrease the probability of hit due to the rapid succession of recoil impulses and the inability of the Soldier to maintain proper sight alignment and sight picture on the target.”

Source: TC-3-22.9 Rifle and Carbine: Headquarters, Department of the Army)

Automatic, even burst mode, is primarily important to assault rifles in order to provide covering and suppressive fire. Those are not about killing people, but rather about pinning them down and stopping them from shooting back. This is mostly about allowing teammates to maneuver into better tactical position, and none of this tends to play a significant role in civilian massacres.

I’ll not go into it here, but to go one step further, the fact is that the effective rate of fire for suppressing and covering fire is also extremely low compared to the max full-auto rates. Check the deeper dive here for more on that.

There really shouldn’t be much more to say on this, but because the gun lobby still puts so much importance on full-auto as a component of ‘real’ assault rifles, there is one thing I guess:

Full-Auto is Easy With Semi-Automatic Rifles:

This has been discussed much more elsewhere, and it's a bit of scope-creep for this article, but for those that don’t dig all the way into the other sections I just want to highlight one more thing: if someone decides they want to go “full-auto” anyway, there isn’t much stopping them from doing it with any semi-automatic assault rifles.

Functionally speaking, the difference between full-auto and semi-automatic fire is a on a gradient. There is no crystal-clear line between useful and useless firing rates, nor is there a clear line of “rpm” that marks where the supposed extra danger of full-auto kicks in. The fact is that selective-fire guns can be fired like semi-automatics, and semi-automatics can actually be fired very much like selective fire ones, and — again speaking in terms of function — there is a lot of overlap possible.

While the civilian versions of military-designed assault rifles are semi-automatic, it is really just a few parts that differ (and those can be readily swapped out by those that can access or make them) and they are otherwise perfectly adapted to support rates of fire all the way up to full-auto. This means they pack a whole lot of potential for scalable lethality.

There are also many rifles, like the Ruger Mini14 mentioned before, that are capable of sustained and effective rapid-fire, but lack the full military optimization, but those too can be used in a similar way. The sustainable part of the lethal combination can be more problematic - but not always. The Ruger Mini14 is famously reliable and has been used in multiple mass murders, even though it is not fully optimized like AR platform rifles are (which is probably why those are so much more popular with spree-killers).

While not absolutely necessary, those optimizations can really start to matter when a shooter is aiming to keep up even that 45-60 rpm firing rate for an extended period of time. But, as noted above: they can also shoot much faster in short bursts and that is a lot more sustainable and less physically challenging for the gun itself.

Really fast shooters can hit a rate more like 5-8 rounds per second, or 300 rpm. This is usually done as "double-taps" or 2 quick shots per target. This approach is far more than the 45-60 of a methodical sustained rapid-fire, and very much on-par with how selective-fire rifles are used. And that is just regular shooting technique - there are modifications (covered elsewhere) and tricks that can ramp up that rate of fire enormously.

Bump-firing is a common trick, and with a bit of practice it can be used to fire semi-autos at rates well into the range of full cyclic rate of fire.

It is pretty trivial to do, and it’s hardly a secrete. There are many, many videos online showing how to do it. Gun guys seem to love showing this off:

Here’s another:

Bump firing can be done with almost any semi-automatic rifle to create what is is effectively full-auto - and with pretty significant control.

All of that is without legal or illegal modifications, such as the bump-stocks used on the AR-15s employed by the killer in the Las Vegas shooting. which resulted in over 400 people shot, more than 800 injured, and 59 people killed, in just about 11 minutes. Bump stocks and many other devices and tricks can drive the firing rate of semi-automatics well into the range of machine guns, and with a bit of searching you can actually see about a million videos on Youtube demonstrating how all this done. You can dig into Assault Rifles: the 3-Part Recipe for Scalable Lethality to see a bit more about the techniques and modifications.

So the fact that civilian assault rifles lack the selective-fire switch doesn’t really mean much at any level. Having a weapon that is perfectly designed and built to support full-auto fire means the barriers to actually using that kind of shooting to kill civilians are minimal. The potential is always readily available, even when true selective-fire weapon are prohibited.

Bringing it Home

So we can circle back around to where we began (no pun intended), but with a much better sense of what that all means and why it matters:

This is not just something I made up by the way - these aspects have been used in varying ways to formulate gun laws in other countries. This definition, and understanding how the various aspects unite to create sustained, effective rapid-fire should give you a much better appreciation for why it is important to think of all semi-automatic assault-type rifles as extremely deadly, not just “military” ones.

It’s much more accurate to see many of them as effectively equivalent to their full military counterparts in most situations, and nearly all situations where public safety and mass shootings are the concerns.

What is perhaps more important would be to consider just how many more rifles should be thought of in the same way, once we start thinking in terms of functional combinations and not focusing so much on the more characteristic appearance of assault rifles. Many less obvious weapons are capable of the same deadly fire, although sometimes less effective, or perhaps less sustainably. They may be more prone to jamming or getting too hot to handle effectively, or problems like that, but remain extremely dangerous. This isn’t speculation. Guns like that are used all the time to murder people.

Nothing about this is will be surprising to most of the pro-assault rifle gun crowd. The fact that assault rifles are so dangerous and are less prone to failure are precisely the reasons they wanted them in the first place.

Do not be baffled by the gun lobby bullshit about what the “real” assault rifles are, or be misled about how well the risks and hazards are really being managed by current legislation, at least here in Canada. Be sure that they are not, not nearly well enough - at least not if we are focusing on the functionality that makes assault weapons truly dangerous.

The bottom line is that civilian assault rifles are a real thing, and the risks are equally real and remain very poorly managed. Saying otherwise is bullshit, plain and simple.

Thoughts about the article? Feel free to drop me a line.